Carina Schlebusch is combining archaeology, genetics and biochemistry with the aim of discovering how human genes have adapted to changing lifestyles over thousands of years. Prehistoric DNA from skeletal remains in Africa can provide answers to questions about diet, disease and survival, and perhaps even offer clues about humanity’s future health.

Carina Schlebusch

Professor of Human Evolution and Genetics

Wallenberg Academy Fellow, grant extended 2024

Institution:

Uppsala University

Research field:

How agriculture spread across the African continent

Homo sapiens emerged on the African continent some 300,000 years ago. This marked the beginning of a phase shaped by both adaptation and expansion, not least during the transition to an agrarian society.

Human genes still carry traces of these changes, so the study of prehistoric DNA is central to our understanding of human evolution.

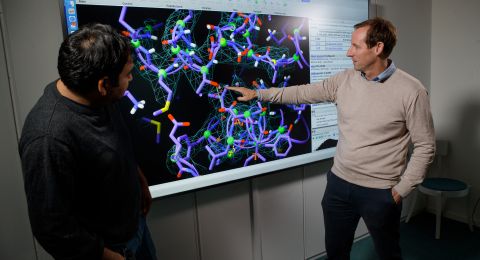

Over the past few years, Schlebusch, who is an evolutionary biologist based at Uppsala University, has studied how agriculture and herding spread across Africa. Genetic data show that it was rarely only ideas that spread. People actually moved and brought their lifestyles with them.

“As the climate warmed, people began to grow crops and keep animals. Everything changed –

how they lived, how communities were organized, and even their biology,” she says.

Focus on health and diet

Her extended Wallenberg Academy Fellow grant enables Schlebusch to deepen her research.

“Now we are searching for tangible traces of what happened when humans adapted to a new lifestyle. It’s the same material, but new questions.”

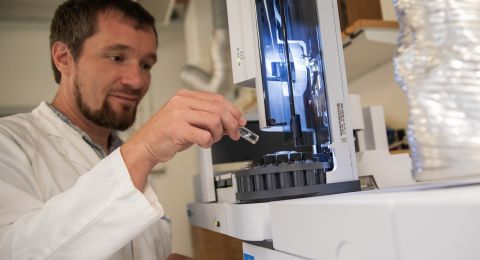

Alongside human DNA, stable isotopes are analyzed to understand diet, metagenomes to identify microbes and pathogens, and proteins in dental plaque that provide pointers to the food that people ate.

“For example, isotopes show whether their diet was rich in meat or plants, and whether crops were wild or cultivated. We’re comparing different periods to see when diets changed and how the body adapted.”

Schlebusch mentions lactose tolerance as a classic example of genetic adaptation.

“In Europe, we saw that the gene for lactose tolerance became common much later than previously thought, probably due to pressure brought on by drought and famine. It will be exciting to see how it was in Africa.”

Prehistoric plagues

Part of the research concerns how new pathogenic organisms emerged. Since humans and animals in Africa have lived in close proximity for long periods and in a varying climate, DNA analyses can reveal how epidemics occurred and how they affected societies.

“We can compare genetic material from before and after an epidemic and see whether certain gene variants became more common. The research can show how people actually adapted to diseases.”

A previous breakthrough came from the study of a seven-year-old boy who lived about two thousand years ago at Ballito Bay in present-day South Africa. Analysis showed that he belonged to a hunter-gatherer population and carried an infection caused by the Rickettsia felis bacterium at the time of his death. It had previously been thought that the bacterium emerged only in modern times and was linked to domestic animals, but the study showed that it had existed long before people began keeping livestock.

It is not about resurrecting the past, but about understanding how people coped with change. Those traces still remain in us.

“This boy lived a short life, suffered a painful illness, and was forgotten for nearly two thousand years. Modern DNA research enables us to tell his story. His life has gained a broader meaning because his preserved genetic material is now used in many different studies.”

Heat and humidity damage DNA

One challenge is extracting well-preserved DNA, since climate and soil composition affect degradation.

“Heat, humidity and acidic soil are devastating; alkaline soils and caves preserve material better. That’s why we often find the best samples in southern and eastern Africa.”

Meanwhile, technological progress is rapid. Schlebusch mentions new methods for drilling samples without heat damaging the DNA and future potential for sequencing even ancient RNA.

“That would open up entirely new ways of studying viruses.”

The research is interdisciplinary and based on collaborations with universities and museums in multiple countries, including South Africa, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Kenya, Democratic Republic of Congo and Madagascar. Schlebusch travels frequently to meet colleagues and partners.

The scientific findings are also shared with local institutions and with people who have participated in previous studies. Bone fragments and teeth bring hidden stories to life with the help of modern technology, which means a lot in societies where written history is often lacking.

Growing up in South Africa, Schlebusch became fascinated by the connection between biology and history.

“I wanted to be an archaeologist, but then became more interested in biology. When I discovered that human history could be studied using genetics, everything fell into place.”

The goal now is to understand how the transition to agriculture affected people’s health and diet and how humans adapted genetically to their new lifestyle. Schlebusch sees parallels with our own time.

“When contemporary hunter-gatherers move into cities, they often develop health problems such as obesity and cardiovascular disease. Our bodies are adapted to scarcity, not abundance. By understanding how our ancestors coped with change, we can better understand our own challenges.”

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström