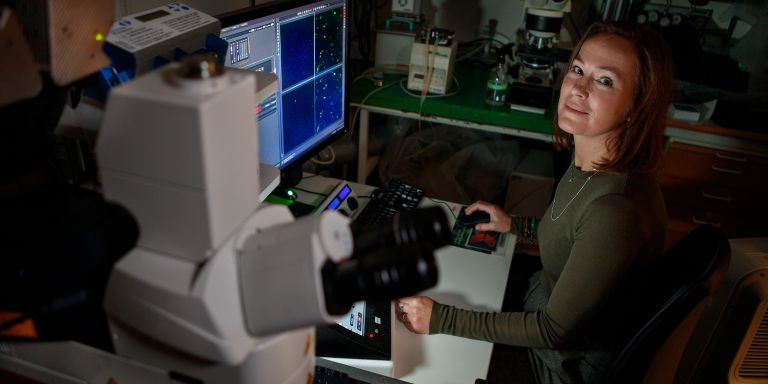

Mia Phillipson

Professor of Physiology

Wallenberg Scholar

Institution:

Uppsala University

Research field:

Medical cell biology. Mapping the functions and behavior of immune cells

Wallenberg Scholar

Institution:

Uppsala University

Research field:

Medical cell biology. Mapping the functions and behavior of immune cells

A woman menstruates about 400 times during her fertile period. Each month, the epithelial lining is expelled and then regenerates, before being expelled again. What is created is a wound that heals very quickly. Phillipson elaborates:

“As I see it, this is a wound healing process that occurs about 400 times in the uterus without scar tissue forming, which is unique. No other part of the body can heal so regularly without leaving scars,” she says.

The endometrium differs in several ways from other parts of the body. One difference is that a very large proportion of cells of the endometrial are immune cells. They are probably there to provide stronger protection against infection, and to help rebuild the lining between menstruations. However, these are only educated guesses, as she points out:

“We do not actually know their exact function or precisely what type of immune cells are involved in the different stages of the menstrual cycle. My hypothesis is that some of these are specially programmed immune cells with the ability to promote healing without scarring.”

Phillipson’s earlier research has shown how immune system cells can change their behavior when different forms of injury occur. Macrophages are one example. Their main task is to deal with invaders and remove damaged cells. But when they are near damaged tissue, they switch on completely different genes that give them the ability to help build new blood vessels and restore blood flow. These functions are crucial for the healing of injuries.

The body’s most common immune cell, the neutrophil, were also demonstrated to be important for the formation of new blood vessels in injured tissue. Following these discoveries, several immune cells are now divided into different subgroups based on their different functions.

“We have now found subgroups of healing neutrophiles and macrophages in the lining of the uterus. We believe that the endometrium – the lining that covers the inner walls of the uterus – has developed the ultimate wound-healing process in the body, and more immune cell subtypes remain to be found. But much work lies ahead before we can know for sure,” she says.

One reason we know so little about the development of the uterine lining is that so few mammals actually menstruate. Humans belong to a group of primates that menstruate, along with a few species of bats, elephant shrews and spiny mice.

But menstruation does not occur naturally in any of the common animal models used in research. The key for researchers may lie in the rare rodent from North Africa: the spiny mouse. In addition to menstruating, it has regenerative abilities. Among other things, it can shed its skin if it gets caught in the teeth of a predator.

“The spiny mouse is extremely good at healing wounds. Just a few days after shedding its skin, it regenerates again. Yet only a handful of researchers have used it in their work.”

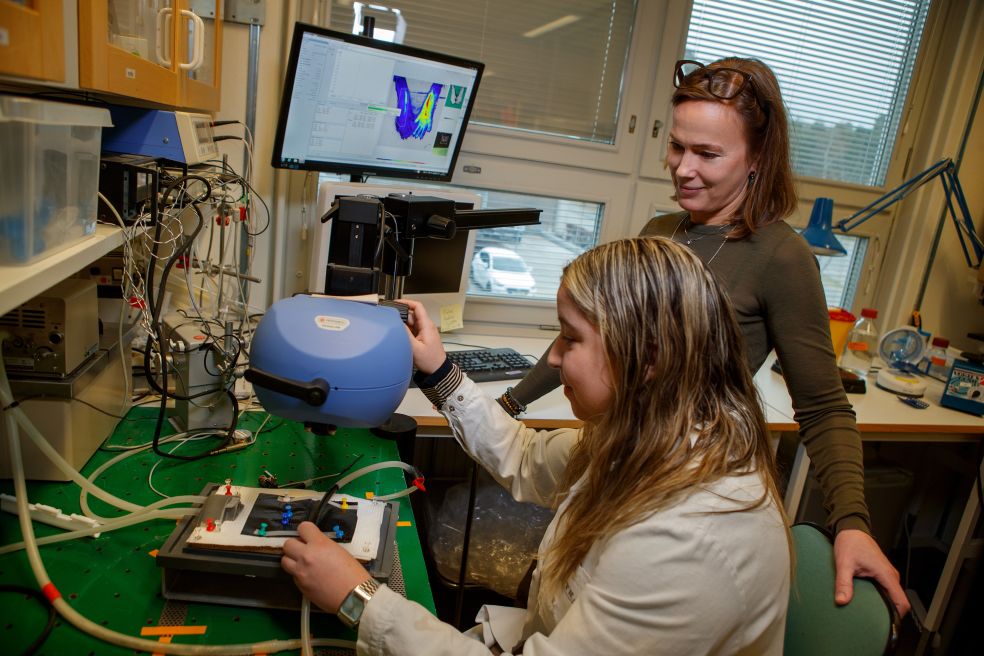

Phillipson’s research team is the first in the country to use the spiny mouse as an animal model. Collaboration with a Portuguese research group has enabled the team to establish the model at Uppsala University. The next step is to confirm the observations made in the spiny mouse in humans. To this end, the team is also collaborating closely with the Uppsala University Akademiska hospital.

In many cases, it is the scarring itself that causes people to die of diseases. So it would be fantastic if we could eliminate it.

Shifting the research focus to humans can improve our understanding of endometriosis, among other things. In this disease, cells from the uterine lining spread to other places in the body, including the peritoneum and ovaries. No one yet knows why this happens, and so there are no effective treatments.

“We also hope to create a better understanding of why some women have excessively heavy menstruation. It may be that they have an impaired healing process in the lining, but we do not yet know if this is so.”

The step from basic research to clinical benefit is usually very long. But Phillipson has managed to take it earlier. Her research on immune system activation has been further developed into a potential treatment for faster wound healing. A company called Ilya Pharma is developing a genetically modified bacterium that produce a signaling substance that increases restorative immune system responses.

“The support of Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation has played a major part in enabling us to go all the way from basic research to application. The foundation’s long-term funding gives us the time needed while also enabling us to patent discoveries along the way.”

Several clinical trials of the company’s products are currently under way, one goal being to investigate if the product can help individuals with SAVI that develop wounds with impaired healing on hands, legs and in the face.

The ability to control the body’s immune cells falls within the scope of immunotherapy. The most well-known examples are cancer treatments where the body’s immune system is used to fight tumors.

“But immune cells have several functions that we should make use of. These include healing of injured tissues, although we then need to understand how to stimulate precisely that function.”

Text Magnus Trogen Pahlén

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström