Advanced organic nanocrystals may become key to the sustainable energy production of the future. As a Wallenberg Academy Fellow, Haining Tian aims to understand how light can drive chemical reactions in the same way as in nature, but using artificial materials.

Haining Tian

Professor of Physical Chemistry

Wallenberg Academy Fellow, grant extended 2024

Institution:

Uppsala University

Research field:

Developing new ideas and constructing systems for solar energy conversion at the molecular level

When the sun shines on Earth, plants and algae store energy through photosynthesis. Recreating this process in technical systems is one of the great challenges of our time. Many research teams therefore dream of breakthroughs in the field known as artificial photosynthesis.

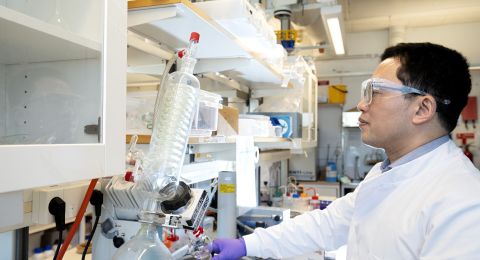

At the Ångström Laboratory in Uppsala, chemist Tian and his research team are developing organic molecular nanocrystals (OMN), which can convert light into chemical energy with high efficiency.

For the reactions to function optimally, the crystals are combined with auxiliary components that capture the charges created by the light and channel them to the proper chemical processes. Together, they form a system in which sunlight can directly drive the production of fuels and other energy‑rich substances.

From polymer dots to organic nanocrystals

The research began with polymer dots – tiny particles of organic polymers, less than 100 nanometers across – that can capture light and initiate chemical reactions.

“That was our first major project,” says Tian. “But we noticed that the catalytic performance of polymers dots highly depends on chain length of polymer, it was difficult to control sometimes.”

The next step was organic nanocrystals with well‑defined molecules that can be fabricated exactly the same way each time.

“With the organic molecule, we can determine the structure very precisely using NMR and mass spectrometry and prepare nanocrystals with a good control. That orderliness is crucial to our understanding of how light affects the material,” says Tian.

Light driving chemistry

The core of the project is a process called symmetry‑breaking charge separation. It sounds theoretical, but in practice it concerns how light energy can create electrical charges in a material and keep them separate, which is essential for driving chemical reactions.

“In all catalytic reactions we need charges in the form of electrons and holes,” Tian explains. “We use solar energy to create them and lead them to the appropriate reaction.”

When light hits the crystal, the electrons gain extra energy and begin moving from one part of the molecule to another. In conventional semiconductors such as silicon, element doping or special interfaces are often required to separate these charges. In Tian’s nanocrystals, however, it happens spontaneously thanks to the molecular packing in the nanocrystal.

Each molecule consists of two parts: a donor (D), which readily donates electrons, and an acceptor (A), which readily receives them. This built‑in D-A structure allows electrons to move in a defined direction when light is absorbed. First, the charge separation occurs within a single molecule. Then the electrons jump between neighboring molecules in the crystal, keeping them apart long enough to power chemical reactions.

If we could convert just one‑tenth of one percent of all the solar energy that reaches Earth, it would be enough to meet society’s needs. It shows why the work is important. This is not a quick fix, but if we succeed it could change everything.

“First, the charges separate within the molecule. Then the electrons move between molecules in the crystal to reach the surface so that we can use them before they recombine,” Tian explains.

This resembles part of natural photosynthesis, where symmetry-breaking charge separation allows light to create charge separation without large energy loss.

Potential for fuels and chemicals

The goal is for the new materials to use sunlight to convert water and carbon dioxide into energy‑rich substances such as hydrogen and carbon‑based fuels.

“We want to produce hydrogen efficiently, and also convert carbon dioxide into useful chemicals using photoredox catalysis” says Tian.

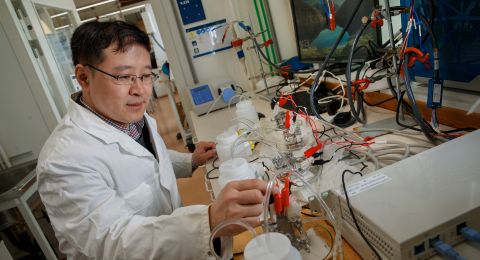

The next step is to use the best materials in a flow‑cell reactor.

“We are building a reactor in which the catalysts are attached to glass chips. Water and carbon dioxide flow over them under illumination. This makes it easier to separate products and control reaction time,” says Tian.

Attaching the catalyst to a surface instead of letting it float in solution gives stability and control. A postdoctoral researcher has been recruited to construct the flow reactor, which will be able to run continuously without the crystals clumping or becoming less active.

“We want to understand every step before scaling up to something of greater practical application.”

Toward artificial photosynthesis

Tian’s work is part of the growing research field of artificial photosynthesis.

“The idea is not new, but methods and materials have become more refined. In the past, researchers tried to use single molecules to imitate nature. Now we build aggregated molecular system that do the same thing – but more efficiently.”

The vision is a carbon‑neutral cycle in which solar energy is stored chemically. Carbon dioxide is used to produce fuels and chemicals, and when these are consumed, the same amount of carbon dioxide is released and can be reused in new reactions. In practice, the system stores solar energy in chemical form.

Progress has been made, but the road to practical applications may still be a long one.

“This is basic research. We know what we can do and what the challenges are, and there is enormous potential if we succeed,” says Tian.

Text Nils Johan Tjärnlund

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Magnus Bergström