Project Grants 2011

Power Papers

Principal investigator:

Magnus Berggren, professor of organic electronics

Co-investigators:

Niclas Solin

Olle Inganäs

Thomas Ederth

Xavier Crispin

KTH Royal Institute of Technology

Lars Wågberg

Innventia AB

Tom Lindström

Institution:

Linköping University

Grant in SEK:

35.4 million over five years

Today’s electronics are manufactured with expensive materials that may also be difficult to recycle. They will soon be replaced by recyclable paper electronics.

Electronics are already being pressed into paper in Norrköping. Among other things, Magnus Berggren and all the researchers, designers, technicians, chemists, and mechanics working with him have made it possible to convert an ordinary printing press into a press for printing electric components on paper. They simply pour electronic ink into the containers that were actually designed for printing ink.

“My colleagues and I started dreaming about this back in 1999, when our lab was completed. We were first in the world in the field of ‘paper electronics’ and initially worked with various plastic structures, polymers. Even then we talked about taking this down to the cellulose level, and with the grant from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, we’re going to be able to do it,” says Magnus Berggren, professor of organic electronics at Linköping University, with conviction.

Smart and environmentally friendly technology

In 1999 the first sheet of paper with electronics was printed, and starting in 2011 the first simple commercial products are now being produced at the PEA facility, an innovation project with basic funding from Vinnova. Forty kilometers of character displays on paper have been manufactured, and a number of companies have been spun off. It is primarily the advertising and security industries that were quick to adopt this technology. In PEA’s entry hall there is a product stand made of paper where the network in the green leaves that decorate the stand are illuminated by light-emitting diodes pressed into the paper.

“Right now we’re working on a pilot project within the framework of ‘Brains and Bricks’ with labels and sensors in collaboration with the construction company Peab and the municipal housing corporation Hyresbostäder,” says Magnus.

In an attempt to avoid moisture and water damage in a newly built housing development, they are using new sensors. They consist of a label of thin foil containing a tiny antenna that transmits information when the level of moisture changes.

“The technology is also environmentally friendly. Our vision is to make everything we produce recyclable,” Magnus Berggren points out.

Similar sensors can be used, for example, to control the temperature in food transports or other production chains.

“I’m truly excited about these sensors. They are the future. In combination with the mobile phone we will be able to easily monitor various processes and find out immediately if something is wrong.”

Paper and muscles

Magnus now wants to take paper electronics to the next level and integrate the electronics in the paper pulp. In order to understand the process properly, he gathered some 30 individuals, including some researchers from the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, for a basic course in making paper with electronic functions.

“At the same time, we had a brainstorming exercise. Of the 111 ideas that emerged we have chosen to move forward with seven or eight.”

One of the ideas was to build in a muscle function in the paper.

“The idea is to be able to apply pressure to the paper or cardboard and change its form or structure. It could fold itself into a box or dissolve into the structure of toilet paper so it can be flushed. In five years or less, I believe, we’ll have achieved this.”

At the same time he admits that it was a huge step to be able to print electronics on paper and that this step is at least as big the last one.

“It’s a challenge. But I believe more and more in the notion of disposable electronics that we can recycle. The vision is to connect paper to the Internet.”

Many areas of application

This technology can be incredibly valuable when it comes to determining the genuineness of currency, bankcards, or tickets.

“We’ve already tried introducing electronics in paper currency. With the help of a mobile phone, in principle we should be able to make Linnaeus (on Swedish bills) blink, thus confirming that the bill is genuine. We have also produced electronic tickets for a special conference. It’s impossible to counterfeit bills if they have to light up,” he says with a smile.

Magnus points out that the collaboration with PEA is important in many ways, including the fact that he can get so close to users.

“As researchers, we’re interested in new ideas that come from customers. We have a fruitful flow of information in both directions,” he emphasizes.

Magnus and his colleagues collaborate closely with the research institute Acreo. They will soon be moving into shared premises in Kåkenhus, the heart of Campus Norrköping. Another key collaborative partner is at Campus Valla in Linköping, Professor Olle Inganäs, who is the one primarily pursuing research on paper batteries.

“We’ve already printed batteries in the same printing press we use for electronics. The idea is to charge the electronic paper with built-in solar cells or maybe by induction,” Magnus Berggren explains.

Text Carina Dahlberg

Translation Donald S. MacQueen

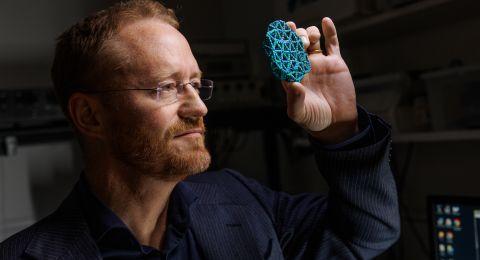

Photo Magnus Bergström

More areas of application

Smart packaging – a sensor determines whether the milk has soured or the meat is off, whether it should be thrown out or can be eaten. This would reduce the amount of food that gets thrown out unnecessarily.

Printed solar cells – can be made of renewable materials but also in new forms, such as a roofing paper that provides heat for the house, or a window film that both dims strong light and converts sunrays into energy.

Proof of authenticity – barcodes that can be hidden under layers of ink to certify that a vaccine or a medicine is genuine, for example.

READ MORE ABOUT

Projekt Grant 2018

Replacing gasoline with paper fuel cells

Project Grant 2014

Making electricity from invisible sunbeams

Wallenberg Scholars

Magnus Berggren