Terje Falck-Ytter is studying whether signs of autism spectrum conditions can be identified during the first years of a child’s life. The plan is to assess 140 infants at one month of age, and then monitor their development up to the age of three.

Terje Falck-Ytter

Professor of Psychology

Wallenberg Academy Fellow, Prolongation grant 2024

Institution:

Uppsala University

Research field:

Developmental psychology, psychological processes in early childhood resulting in neuropsychiatric conditions such as autism, ADHD or language impairment

It is currently possible to reliably diagnose autism spectrum conditions at roughly two to three years. Early diagnosis is necessary for early intervention, which has been found to have positive effects on autistic children and their families. But Falck-Ytter is at pains to point out that he is not aiming to diagnose infants.

“We won’t be able to say this or that infant will ultimately receive a diagnosis at the age of three. In the initial phase, the study aims to identify developmental mechanisms at group level that yield new insights. We want to understand how things fit together. The hypothesis is that basic sensory signals are processed in a different way early in life in autism. Although outside the scope of this project, eventually we hope to improve the methods so one day they can be used to make a clinical diagnosis.”

Falck-Ytter is a professor of psychology at Uppsala University. He has long experience of studying young children likely to be diagnosed with autism or ADHD.

In 2011 he started a study entitled Early Autism Sweden study (EASE), which is a collaboration between Uppsala University and Karolinska Institutet. The youngest children in that project are four-five months old at study entry; many are ten months. As a Wallenberg Academy Fellow he will now be studying children who are as young as one month old.

“Children’s development is highly complex. The difference between the mental processes of a one-month-old infant and a baby aged ten months is greater than that between a one-year-old and a ninety-year-old,” Falck-Ytter explains.

“The Academy Fellow grant gives me a unique opportunity to study fundamental aspects of infant development, with the emphasis on individual differences in brain development and behavior. I hope that the research will ultimately have clinical applications.”

Early studies vital

Since the EASE study started, that and other studies have led researchers to conclude that children should be studied as early as possible.

“Children develop in a complex interaction between genetic predisposition and environment. It’s a dynamic system of constantly growing complexity. It’s a good idea to study it early to gain a clear picture of the system and to identify patterns.”

Both genetic research and animal models support the contention that early development should be studied in the context of autism, probably even before the child is born.

“It might sound extreme to test infants, but we have child-friendly methods and good experience of children who are slightly older. Their parents have also found it to be of value.”

The new study is recruiting children with siblings or parents already diagnosed, since, due to the high heritability, this increases the likelihood that they too will be diagnosed with an autism spectrum condition.

It is hoped that the project can begin receiving infants by fall 2021. A total of 110 infants with relatives with a diagnosis will be recruited, together with 30 children with no known genetic predisposition. It is a complex interdisciplinary study involving a broad spectrum of expertise.

“The idea of the project is to examine basic sensory processes in the brain, how children react to auditory and visual cues, for instance. How children as young as one month old process simple impressions to make sense of the world in which they find themselves.”

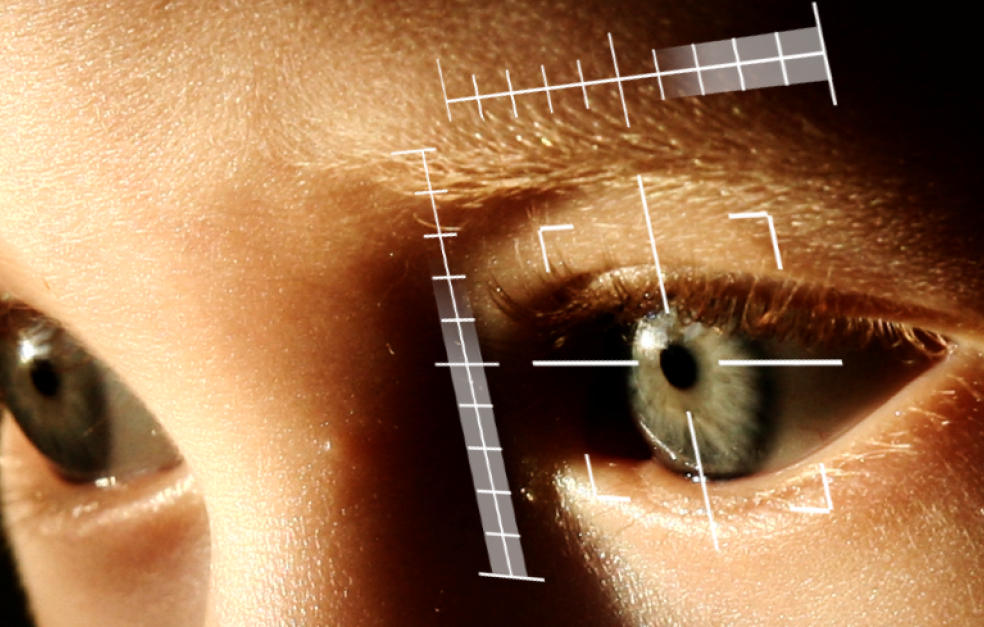

Pupil size revealing

He explains how they put a “cap” fitted with electrodes (EEG) on the child’s head. This can measure how the child’s brain filter the information to which they are exposed.

“The hypothesis is that children on the autism spectrum pay just as much attention each time they receive information that is repeated, whereas others filter out repetitions, freeing up resources to take in other impressions.”

Pupil measurement is another method the researchers will be using. Studies of 10-month-old children have shown that changes in pupil size when a light is shone on it are associated with subsequent autism diagnosis and symptom level.

“We know that it’s linked to a well-known neural pathway. If we can see it in very young children, it will also be easier to find links in animal models that can then be investigated. But the pupil is not only sensitive to light; it also reflects attention. So it’s a simple measure revealing two entirely separate processes that we can study.”

Magnetic resonance imaging, questionnaires and other studies will also be used. When children are examined at the age of two to three, they will be seen by psychologists specializing in autism, language development, general development and ADHD-related symptoms.

“There are many borderline cases, such as children with autistic traits but without a formal diagnosis, as well as children who are diagnosed with multiple conditions. We’re studying many aspects of development to try to gain an overall picture.”

Falck-Ytter also has practical experience of children on the autism spectrum. He moved to Uppsala from Oslo to be trained as a clinical psychologist. When he was working on his master’s thesis, his supervisor, Professor Claes von Hoffsten, put him in touch with a research project examining children’s ability to understand the actions of others. The findings of his thesis were later published in Nature Neuroscience.

“It was easy then to get the idea that research was a walk in the park.”

He later completed his clinical residency at the Habilitation and Autism Center in Uppsala.

“I worked with the clinical autism team in parallel with my PhD studies. Habilitation work was really enjoyable and rewarding. Research is also great fun, but is not particularly easy; it requires a great deal of patience.”

Text Carina Dahlberg

Translation Maxwell Arding

Photo Linnea Hamrefors, David Naylor, Pär Nyström, Lars Wallin